[You cannot] detect your personality and its decisions in the course of being created by your experience. You know only that you ingest the present tense and excrete it as a narrative in the past.

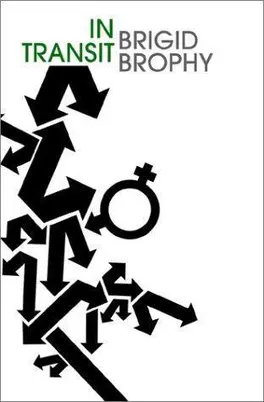

I have never read anything this dense with wordplay, puns and sheer linguistic playfulness. I did not understand close to all of it but all I need to continue reading to the next paragraph and experience Brigid Brophy doing something else charmingly unspeakable to the English language (and sometimes other ones as well). There is almost a tactile physicality to the prose in some parts. Is this felt joy like what people who like Joyce feel? I feel like the insufferability of my writing may increase just by having read this. The text rending the rendered text on my website unreadable. I flail to imitate it, my sincerest fattery.

Okay, I’ll stop with that. The novel starts very philosophically, with the narrator—born in Ireland but moved to Britain when they were young—wandering around an airport lounge as their mind similarly wanders, basking in the most liminal and modern of public spaces to muse on the concept of being “in transit”. Of a space of movement, of transition, of the crossing of boundaries, a space international in character and (the novel being written in the 60s) a state of being that is starting to be opened to more than just the upper classes.

In this state several peculiar things start to happen to our narrator. They undergo what they describe as “linguistic leprosy”, a state that mostly results in a flood of multilingual puns in major European languages. The relationship with the Irish language and Irishness here is interesting. The narrator is not comfortable with the language. They can not wield it deftly or easily and are reduced to making the old tired jokes about how odd the spelling conventions are. There is a lamentation in this. They have had exposure to it to think they should perhaps know it a bit more. This is put out to leaving at a young age but this rings quite true as someone who has lived in Ireland her entire life as well. Along with the leprosy there is the pain of a phantom tongue that was never really known. Joyce comes to mind again, though from reputation more than experience. The only Joyce that I’ve read is one or two stories from Dubliners. But with Joyce, Brophy and Ireland’s general reputation (or at least the reputation we tell ourselves that we have) for great works of English poetry and literature, does the ungaelicised mind seek to master its foreign mother tongue, to turn the tables on the colonisation of language?

The novel takes a turn towards farce in the second part, when the protagonist (gender previously hidden, as the book points out itself, with the use of the personal pronoun I) realises that somehow, ridiculously they have forgotten what sex they are, and tries to–within the bounds of polite public behaviour—figure out what’s going on downstairs. The sex marker on the passport has been (in)conveniently blotched by a coffee stain, their clothes are oh-so-modern, gender neutral and loose fitting, if they have breasts they are too small to be noticeable, reading the porn novel that they had in their bag and seeing if they relate to the Story of Oc’s Tongue as voyeur or self-insert and then stop just short of groping themselves in public before they realise that the man sitting across from them in the airport café is starting at them like they are a lunatic. This results in an escalating series of misadventures up to and including ending up on a gameshow where they have to guess someone’s kink live on air.

One might expect the exploration of gender to have aged poorly, but other than (admittedly fairly gaping from a contemporary perspective) lack of consideration of the concept of being trans or intersex I think it’s great and, more importantly, very funny. What has aged somewhat more poorly is the language around race that the book uses. It’s not hateful, but the earnest use of the word “oriental” and the in-passing exoticisation of the few non-white characters in the book is less than ideal.

The book transforms itself again towards the end, splitting our narrator into the dual personalities of Patric{k/ia} and then branching further off to focus on the experiences of various other characters as a socialist, egalitarian revolution takes control of the airport lounge. I must admit I didn’t like this section as much. It feels like the novel over-stays its welcome a bit, which is a shame, but I did enjoy the choose-your-own-adventure ending.