The Train Fiend

I feel so grateful to the man who invented the “Traveller’s” typewriter.

Mina Harker, expressing her love for her laptop.

Applying modern labels and understandings of people to the past is iffy and and remains so when applied to fictional characters who were certainly never written with those as-yet non-existent concepts in mind but also it’s fun so I’m going to do it. Mina Harker (née Murray) is an autistic, bisexual, and cool as hell.

None of what I’m going to say is a particularly original idea and much of what I’m drawing from here is from the general milieu of the Dracula Daily fanbase. This was, of course, a large part of the appeal of Dracula Daily; not just a novel way to read a classic book but also a participatory exercise in going through that work and evolving a fandom understanding of it as it progresses, with all the tenuous headcanoning that such things involve.

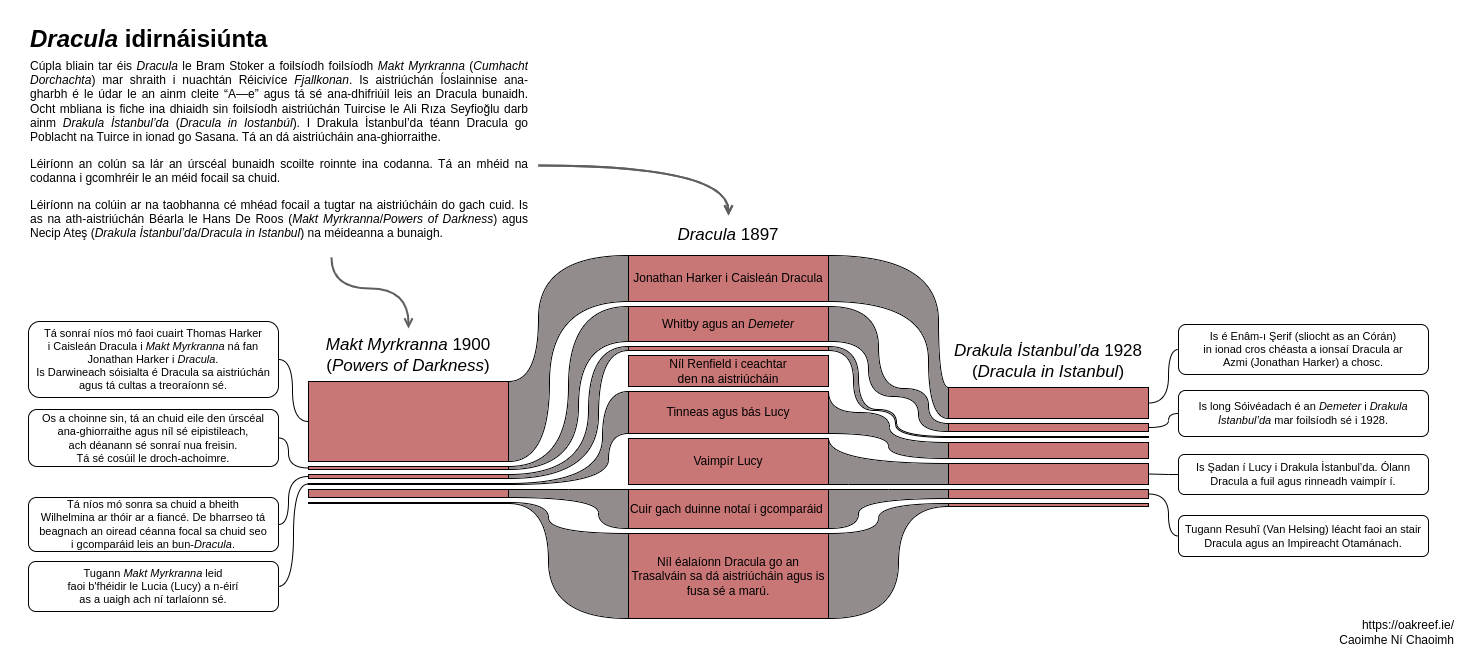

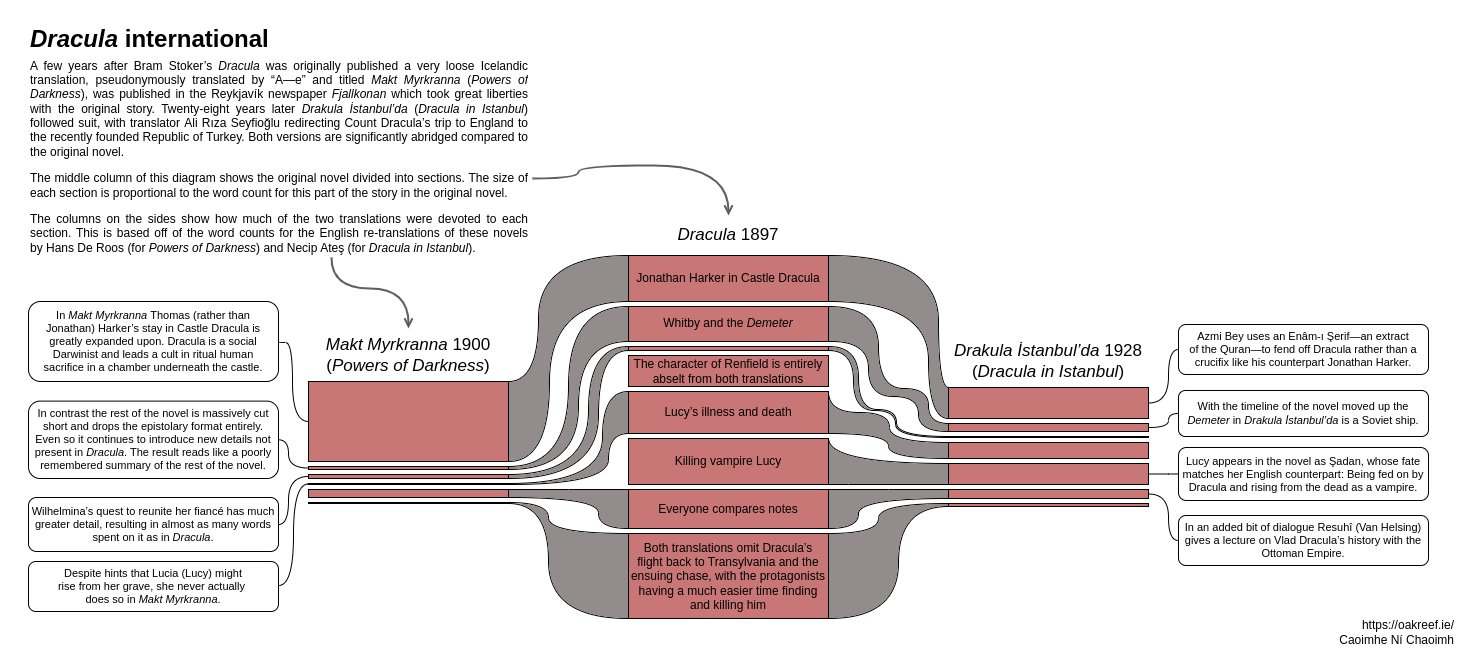

Dracula is Gothic fiction wherein the ancient horror is defeated and soundly routed by modernity. Our heroes are doctors and solicitors (and a rich Texan who fancies himself a cowboy) and an important weapon in the arsenal used to defeat the count himself is meticulous note-taking. And it is Mina who transcribes, edits, organises and distributes these notes. Within the fiction it is she who creates the manuscript that is the text of the novel itself and makes carbon copies to provide to the other protagonists. She habitually organises and sorts information and while she often frames it as making herself useful to her husband1 she displays a clear knack and enthusiasm for doing so.

“When does the next train start for Galatz?” said Van Helsing to us generally.

“At 6.30 tomorrow morning!” We all started, for the answer came from Mrs. Harker.

“How on earth do you know?” said Art.

“You forget or perhaps you do not know, though Jonathan does and so does Dr. Van Helsing that I am the train fiend.”

“I am the train fiend”?! This girl autistic as hell.

Mina is also the one who sits down and logically deduces Dracula’s escape plan from everyone’s scattered notes and observations, writing it out her evidence and conclusions point by point.

Ground of inquiry. Count Dracula’s problem is to get back to his own place.

(a) He must be brought back by someone, This is evident; for had he power to move himself as he wished he could go either as man, or wolf, or bat, or in some other way. He evidently fears discovery or interference, in the state of helplessness in which he must be confined as he is between dawn and sunset in his wooden box.

(b) How is he to be taken? Here a process of exclusions may help us. By road, by rail, by water?

[…]

Van Helsing says that Mina has a man’s brain and a woman’s heart1. While this is meant simply as a compliment of her faculties1 the fact that her analytical nature is framed as inherently masculine reminds me of the (nonsense) extreme male brain theory of autism which is rooted in notions of men being naturally more systemising and women being naturally more empathising. This is starting to bend towards me just documenting some free association so I will move on to Mina being gay.

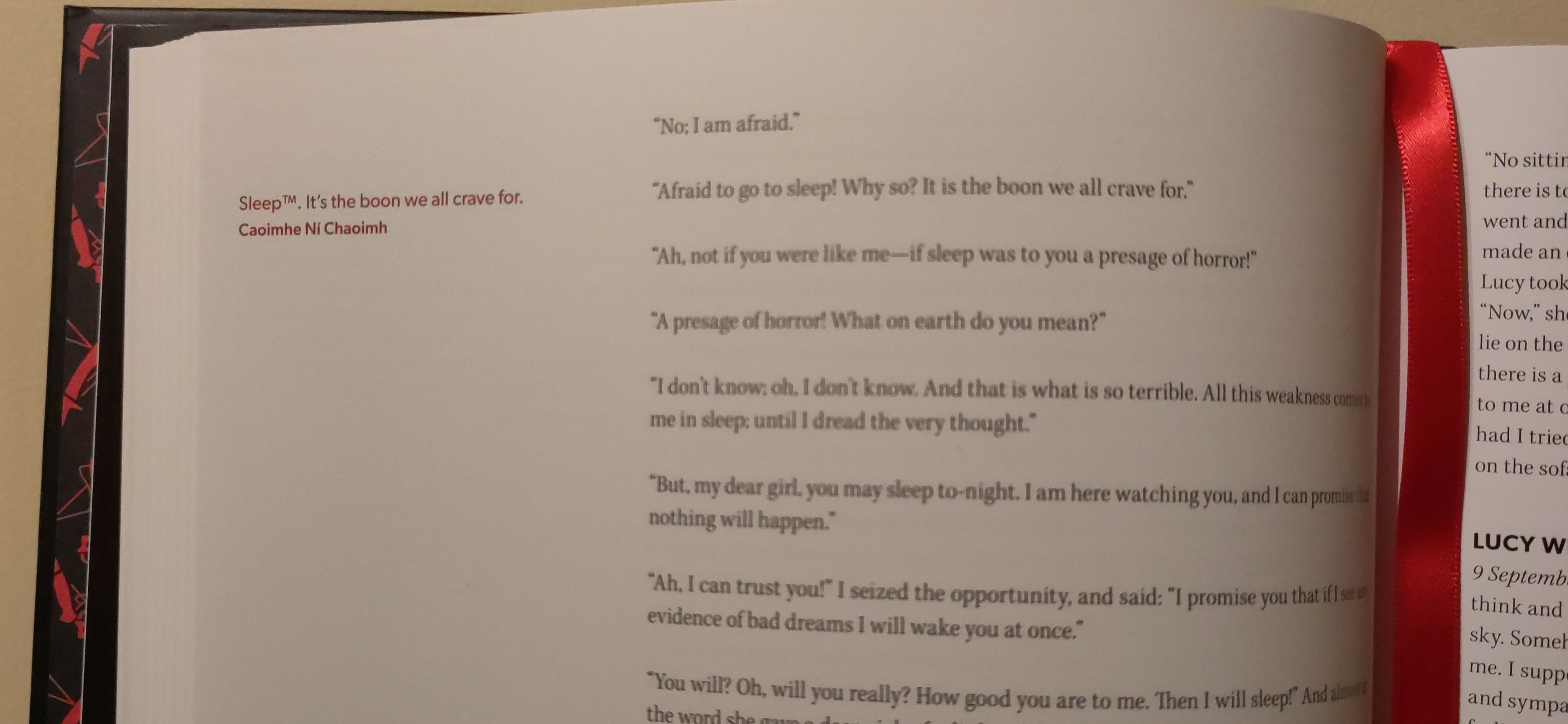

Mina and Lucy in the book have a classic romantic friendship, gushing and fawning over each other to a degree that is difficult not read as somewhat sapphic to a modern reader. Mina takes care of Lucy while she is being secretly preyed upon by Dracula, and while she sleeps Mina notes how beautiful she is, thinking about how it could make someone fall in love with her, about sex outside of marriage, and about the idea of women being able to make marriage proposals1.

Lucy is asleep and breathing softly. She has more colour in her cheeks than usual, and looks, oh, so sweet. If Mr. Holmwood fell in love with her seeing her only in the drawing room, I wonder what he would say if he saw her now. Some of the “New Women” writers will some day start an idea that men and women should be allowed to see each other asleep before proposing or accepting. But I suppose the “New Woman” won’t condescend in future to accept; she will do the proposing herself. And a nice job she will make of it, too! There’s some consolation in that. I am so happy tonight, because dear Lucy seems better.

Later, not having seen Lucy in some time and unaware of her rapid deterioration, Mina sends a letter to Lucy that directly compares the love between her and her husband to the love between her and Lucy and that she could, would, has, does and will love her.

Jonathan asks me to send his “respectful duty,” but I do not think that is good enough from the junior partner of the important firm Hawkins & Harker; and so, as you love me, and he loves me, and I love you with all the moods and tenses of the verb, I send you simply his “love” instead. Goodbye, my dearest Lucy, and all blessings on you.

The novel—the manuscript compiled by Mina herself—emphasises the tragedy of this goodbye and this expression of love by noting that this letter was not opened by Lucy before her death.

Also her favourite spot to hang out in on her holiday in Witby is the graveyard so she’s pretty goth, too.